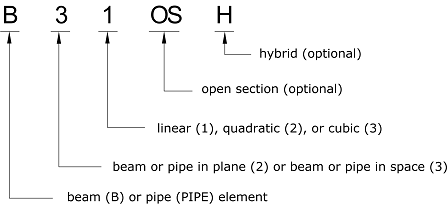

Naming Convention

Beam elements in

Abaqus

are named as follows:

For example, B21H is a planar beam that uses linear interpolation and a hybrid

formulation.

ProductsAbaqus/StandardAbaqus/ExplicitAbaqus/CAE Naming ConventionBeam elements in

Abaqus

are named as follows:

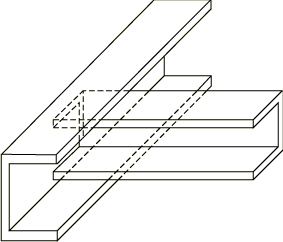

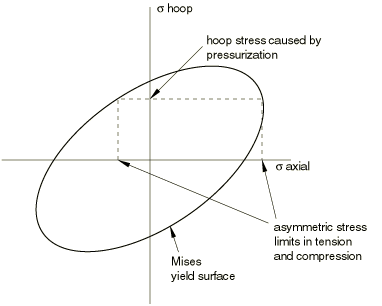

Euler-Bernoulli (Slender) BeamsEuler-Bernoulli beams (B23, B23H, B33, and B33H) are available only in Abaqus/Standard. These elements do not allow for transverse shear deformation; plane sections initially normal to the beam's axis remain plane (if there is no warping) and normal to the beam axis. They should be used only to model slender beams: the beam's cross-sectional dimensions should be small compared to typical distances along its axis (such as the distance between support points or the wavelength of the highest mode that participates in a dynamic response). For beams made of uniform material, typical dimensions in the cross-section should be less than about 1/15 of typical axial distances for transverse shear flexibility to be negligible. (The ratio of cross-section dimension to typical axial distance is called the slenderness ratio.) Load stiffness for pressure loads is not included for these elements. InterpolationThe Euler-Bernoulli beam elements use cubic interpolation functions, which makes them reasonably accurate for cases involving distributed loading along the beam. Therefore, they are well suited for dynamic vibration studies, where the d'Alembert (inertia) forces provide such distributed loading. The cubic beam elements are written for small-strain, large-rotation analysis. They may not be appropriate for torsional stability problems due to the approximations in the underlying formulation and cannot be used in analyses involving very large rotations (of the order 180°); quadratic or linear beam elements should be used instead. Mass FormulationThe Euler-Bernoulli beam elements use a consistent mass formulation. Rotary inertia for twist around the beam axis is the same as for Timoshenko beams. For details, see Mass and inertia for Timoshenko beams. Any additional inertia defined for these elements (see Adding Inertia to the Beam Section Behavior for Timoshenko Beams) is ignored. Timoshenko (Shear Flexible) BeamsTimoshenko beams (B21, B22, B31, B31OS, B32, B32OS, PIPE21, PIPE22, PIPE31, PIPE32, and their “hybrid” equivalents) allow for transverse shear deformation. They can be used for thick (“stout”) as well as slender beams. For beams made from uniform material, shear flexible beam theory can provide useful results for cross-sectional dimensions up to 1/8 of typical axial distances or the wavelength of the highest natural mode that contributes significantly to the response. Beyond this ratio the approximations that allow the member's behavior to be described solely as a function of axial position no longer provide adequate accuracy. By default, Abaqus assumes that the transverse shear behavior of Timoshenko beams is linear elastic with a fixed modulus and, therefore, independent of the response of the beam section to axial stretch and bending. In Abaqus/Standard, B31 and B32 elements that reference meshed cross-sections might also have full coupling between the section strains (axial stretch, transverse shear, torsion, and bending). Elements with full coupling can accurately characterize the response of beams that are made out of composite materials, such as wind turbine rotor blades. The response of such elements is still linear elastic, but the transverse shear behavior and axial stretch, torsion, and bending cannot be separated (see Defining the Stiffness and Mass Properties for Meshed General Beam Sections below). For most beam sections Abaqus calculates the transverse shear stiffness values required in the element formulation. You can override these default values as described below in Defining the Transverse Shear Stiffness and the Slenderness Compensation Factor. The default shear stiffness values are not calculated in some cases if estimates of shear moduli are unavailable during the preprocessing stage of input; for example, when the material behavior is defined by user subroutine UMAT, UHYPEL, UHYPER, or VUMAT. In such cases you must define the transverse shear modulus for the material (see Defining the Elastic Transverse Shear Modulus) or the transverse shear stiffness for the section as described below. The Timoshenko beams can be subjected to large axial strains. The axial strains due to torsion are assumed to be small. In combined axial-torsion loading, torsional shear strains are calculated accurately only when the axial strain is not large. Defining the Stiffness and Mass Properties for Meshed General Beam SectionsYou can define the stiffness and mass properties for meshed general beam sections with or without full coupling among section strains. Without full coupling, the transverse shear behavior of Timoshenko beams is independent of the response of the beam section to axial stretch and bending, as is the case for other section types. Therefore, you define the transverse shear stiffness behavior separately. With full coupling among section strains, you define 21 values of a symmetric 6 × 6 stiffness matrix that relate the six-component section strain vector to the six-components' section forces and moments vector. This definition includes the transverse shear behavior. In both cases, you define the mass properties separately. Typically, you do not define the stiffness and mass properties for meshed general beam sections manually. Instead, you may define and analyze a two-dimensional mesh of the cross-section geometry (optionally with 3-DOF warping elements to capture all potential coupling effects) with proper material assignments in Abaqus/Standard. Such a preliminary analysis generates a jobname.bsp file that contains the options to define the section stiffness and mass properties and that you can include to associate these definitions with a general beam section (see Meshed Beam Cross-Sections). Input File Usage Use the following options to define the section stiffness and mass properties for meshed general beam sections without full coupling (to define the transverse shear behavior, see Defining the Transverse Shear Stiffness and the Slenderness Compensation Factor below): BEAM GENERAL SECTION, SECTION=MESHED SECTION STIFFNESS , , , , SECTION INERTIA , , , , , Use the following options to define the section stiffness and mass properties for meshed general beam sections with full coupling between the section strains, including the transverse shear behavior: BEAM GENERAL SECTION, SECTION=MESHED SECTION STIFFNESS, FULL COUPLING , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , SECTION INERTIA , , , , , Use the following options to associate the meshed beam general section definition with the stiffness and mass properties that you computed with a beam section generate procedure: BEAM GENERAL SECTION, SECTION=MESHED INCLUDE, INPUT=jobname.bsp Abaqus/CAE Usage Defining meshed general beam sections is not supported in Abaqus/CAE. Transverse Shear Stiffness DefinitionThe effective transverse shear stiffness of the section of a shear flexible beam is defined in Abaqus as where is the section shear stiffness in the -direction; is a dimensionless factor used to prevent the shear stiffness from becoming too large in slender beam elements; is the actual shear stiffness of the section; and are the local directions of the cross-section. The have units of force. The dimensionless factors are always included in the calculation of transverse shear stiffness and are defined as where l is the length of the element, A is the cross-sectional area, is the inertia in the -direction, is the slenderness compensation factor (with a default value of 0.25), and is a constant of value 1.0 for first-order elements and 10−4 for second-order elements. For meshed cross-sections the above expressions change to If the meshed cross-sections exhibit full coupling between the section strains, no slenderness compensation is applied; that is, . You can define the or as described below. If you do not specify them, they are defined by or where G is the elastic shear modulus or moduli and A is the cross-sectional area of the beam section. Abaqus calculates the transverse shear stiffness, or , only once at the beginning of the analysis based on the initial value of G. Initial temperature and field variable dependencies of G are considered. Any changes to the transverse shear stiffness that occur due to changes in the material stiffness during the analysis are ignored. The shear factor k (Cowper, 1966) is defined as:

When a beam section definition integrated during the analysis is used (see Using a Beam Section Integrated during the Analysis to Define the Section Behavior) or when a general beam section definition is used with a material definition (see Using a General Beam Section to Define the Section Behavior), G is calculated from the elastic material definition used with the section. When a general beam section definition is used without a material definition (see Using a General Beam Section to Define the Section Behavior), you provide G as part of the beam section data. Defining the Transverse Shear Stiffness and the Slenderness Compensation FactorYou can define the transverse shear stiffness for beam sections integrated during the analysis and general beam sections. In the case of two-dimensional beams, you can input a single value of transverse shear stiffness (that is, ). For meshed cross-sections, you define the shear stiffnesses in the first and second directions ( and , respectively) and a coupling term for the two directions ( ). In the case of full coupling between the section strains, you define the section stiffness and specify the transverse shear stiffness, along with the stiffness for axial stretch, torsion, and bending and the coupling stiffnesses (see Defining the Stiffness and Mass Properties for Meshed General Beam Sections). When you define the transverse shear stiffness, you can also define the slenderness compensation factor. The default value for the slenderness compensation factor is 0.25. If you provide a slenderness compensation factor value, you must also provide the values of the shear stiffness . In the case of first-order elements, you can define the slenderness compensation factor by including the label SCF. Abaqus then uses a slenderness compensation factor of , and any values of that you specify are ignored. Instead, the values are calculated from the elastic material definition. The transverse shear stiffness is not relevant to Euler-Bernoulli beam elements for which the transverse shear constraints are satisfied exactly. Input File Usage Use both of the following options to define the transverse shear stiffness for beam sections integrated during the analysis: BEAM SECTION TRANSVERSE SHEAR STIFFNESS Use both of the following options to define the transverse shear stiffness for general beam sections: BEAM GENERAL SECTION TRANSVERSE SHEAR STIFFNESS Abaqus/CAE Usage To define transverse shear stiffness for beam sections integrated during the analysis: Property module: beam section editor: Section integration: During analysis: Stiffness: toggle on Specify transverse shear To define transverse shear stiffness for general beam sections: Property module: beam section editor: Section integration: Before analysis: Stiffness, toggle on Specify transverse shear InterpolationAbaqus provides finite axial strain, shear flexible beams with linear and quadratic interpolations. Their formulation is described in Beam element formulation. Element types B21, B31, B31OS, PIPE21, PIPE31, and their hybrid equivalents use linear interpolation. These elements are well suited for cases involving contact, such as the laying of a pipeline in a trench or on the seabed or the contact between a drill string and a well hole, and for dynamic versions of similar problems (impact). Element types B22, B32, B32OS, PIPE22, PIPE32, and their hybrid equivalents use quadratic interpolation. Mass FormulationThe linear Timoshenko beam elements use a lumped mass formulation by default. The quadratic Timoshenko beam elements in Abaqus/Standard use a consistent mass formulation, except in dynamic procedures in which a lumped mass formulation with a 1/6, 2/3, 1/6 distribution is used. For details, see Mass and inertia for Timoshenko beams. The quadratic Timoshenko beam elements in Abaqus/Explicit use a lumped mass formulation with a 1/6, 2/3, 1/6 distribution. Using a Consistent Mass Matrix in Abaqus/StandardAlternatively, in Abaqus/Standard you can use the McCalley-Archer consistent mass matrix based on the cubic interpolation of deflections and quadratic interpolation of rotations. Input File Usage Use the following option for linear Timoshenko beam elements with beam sections integrated during the analysis: BEAM SECTION, LUMPED=NO Use the following option for linear Timoshenko beam elements with general beam sections: BEAM GENERAL SECTION, LUMPED=NO Abaqus/CAE Usage Use the following option for linear Timoshenko beam elements with beam sections integrated during the analysis: Property module: beam section editor: Section integration: During analysis: Stiffness tabbed page: toggle on Use consistent mass matrix formulation Use the following option for linear Timoshenko beam elements with general beam sections: Property module: beam section editor: Section integration: Before analysis: Stiffness tabbed page: toggle on Use consistent mass matrix formulation Rotary Inertia Treatment and Additional Beam InertiaBy default, the exact (anisotropic with displacement-rotation coupling) rotary inertia is used for Timoshenko beams. Optionally, an uncoupled isotropic approximation to the rotary inertia can be used. See Rotary Inertia for Timoshenko Beams for further details. The exception to this rule is the static procedure with automatic stabilization (see Static Stress Analysis), where the mass matrix for Timoshenko beams is always calculated assuming isotropic rotary inertia, regardless of the type of rotary inertia specified for the beam section definition (see Rotary Inertia for Timoshenko Beams). In some structural applications the beam element may be a one-dimensional approximation of a structure with complex cross-sectional geometry and mass distribution. In such a cross-section there may be inertia contributions that represent heavy machinery, cargo loaded in a ship compartment, fluid-filled ballast tanks, or any other mass distributed along the length of the beam that is not part of the beam's structural stiffness. In such cases you can define additional mass and rotary inertia associated with the beam section properties. Multiple masses per unit length (with location other than the origin of the beam cross-section) and rotary inertias per unit length can be specified. Mass proportional damping (alpha or composite damping) associated with this additional inertia can also be specified. Abaqus uses the mass weighted average (based on the material damping and the added inertial damping) for the element mass proportional damping. See Material Damping for details. Additional Inertia due to Immersion in FluidWhen a beam is fully or partially submerged, the effect of the surrounding fluid can be modeled as an additional distributed inertia on the beam. See Additional Inertia due to Immersion in Fluid for details. Warping (Open-Section) BeamsWhen modeling beams in space, a further consideration arises from the possible warping of the beam's cross-section under torsional loading. For all but circular sections the beam's cross-section deforms out of its original plane when subject to torsion. This warping deformation modifies the shear strain distribution throughout the section. Open sections typically twist very easily if warping is not prevented, especially if the walls that form the beam section are thin. Constraint of this warping at certain points along the beam (such as where the beam is built into some other member, Figure 1, or into a wall) is then a major determinant of the beam's overall torsional response.  Element types B31OS, B32OS (and their “hybrid” equivalents) have the warping magnitude, w, as a degree of freedom at each node; they are available only in Abaqus/Standard. In these elements Abaqus/Standard assumes that the warping of the cross-section follows a certain pattern as a function of position in the cross-section (Abaqus calculates this warping pattern if you have specified a standard library section or an “arbitrary” section): only the warping magnitude varies with position along the beam's axis. These elements are meant for the analysis of thin-walled open sections in which warping constraints play a role and the axial strains due to warping cannot be neglected. Examples of such open sections that may warp in this fashion are the I-section, channel section, hat section, and any open arbitrary section. In the other beam element types warping is considered unconstrained and any axial stress due to warping is neglected; torsional behavior is not represented adequately when these element types are used with thin-walled, open sections. In general, the warping magnitude can be continuous only when the beam axis is continuous through a node and the beam cross-section is the same on both sides of the node. Thus, if open-section members intersect at a node (such as the cross-member of a vehicle chassis abutting a longitudinal member, Figure 1), separate nodes may have to be used for the intersecting members with different axial directions and appropriate constraints must be chosen for the warping amplitudes in each member at this point. The choice of these constraints is a matter of detail of the local construction. For example, if the joint is reinforced, warping may be prevented; therefore, degree of freedom 7 should be fully constrained with a boundary condition on the appropriate members at the joint. “Pipe” ElementsThe pipe elements in Abaqus assume a hollow circular section. The internal stress caused by internal or external pressure loading in the pipe is included in these elements so that on the pipe cross-section a point under tension has different yield than a point under compression (Figure 2), thus causing an asymmetry in the section's response to inelastic bending. Two formulations are available for pipe elements in Abaqus. The thin-walled pipe formulation assumes constant hoop stress across the cross-section and neglects the radial stress, whereas thick-walled pipes (available only in Abaqus/Standard) allow the hoop and radial stress components to vary across the cross-section.  The hoop stress in thin-walled pipe elements is computed as the average stress in equilibrium with the internal and external pressure loading on the pipe section. For the thin-walled formulation, an integration rule with one point through the thickness suffices to obtain an accurate solution. For thick-walled pipes, the hoop stress and radial stress variation under applied internal and/or external pressure are calculated using Lamé’s equations. The constitutive calculations at each material point take into account the imposed hoop and radial stress values to determine the structural response. A two-dimensional integration rule is used for thick-walled pipes to capture the effect of stress variation across the section accurately. “Hybrid” BeamsHybrid beam element types (B21H, B33H, etc.) are provided in Abaqus/Standard for use in cases where it is numerically difficult to compute the axial and shear forces in the beam by the usual finite element displacement method. This problem arises most commonly in geometrically nonlinear analysis when the beam undergoes large rotations and is very rigid in axial and transverse shear deformation, such as a link in a vehicle's suspension system or a flexing long pipe or cable. The problem in such cases is that slight differences in nodal positions can cause very large forces, which, in turn, cause large motions in other directions. The hybrid elements overcome this difficulty by using a more general formulation in which the axial and transverse shear forces in the elements are included, along with the nodal displacements and rotations, as primary variables. Although this formulation makes these elements more expensive, they generally converge much faster when the beam's rotations are large and, therefore, are more efficient overall in such cases. References

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||